Preface 📖

A submission to the Straits Times forum on the innocuous issue of improving people’s safety 🦺 This leads to a combative discussion on the prickly business of appraising a human 💲🏷️

- Preface 📖

- Context 🛈

- The Submission 📤🗞️

- Comments ⌨️

- A Critique Of Prevalent Sentiment

- The Price Of Life 🔖⛑️🧮

- Final Remarks 🏁

- Reflections 📔

- Further Resources 🗃️

- Footnotes 📝

- Extra: AI Response

Context 🛈

In Singapore, the total foreign (neither citizens nor permanent residents) workforce was around 1.4 million in December 2022, at around 40% of the total workforce. With one of the lowest fertility rates in the world, Singapore has been increasingly reliant on foreigners in sustaining employment and productivity growth. Of the foreign workforce, a large proportion work in blue-collar sectors like construction, manufacturing and marine shipyard. Locals are very averse to working in these industries due to poor working conditions and societal perception. The migrant workers are often transported at the back of lorries, like this.

This is just one aspect of these migrant workers’ working/living conditions, which are commonly deemed by the public as dismal and in need of improvement. In past years there have been several new regulations improving their transport safety, but they are viewed by many as piecemeal, and insufficient to uphold the workers’ dignity and rights. Moreover, for the past 5 years, people onboard lorries comprise about 4 percent of the total annual injuries from road traffic accidents.

Current affairs: On the consecutive days 18 and 19 July, 2 accidents occurred which injured a total of 37 migrant workers (18 + 19 = 37 🤔) who were being transported on lorries. The undercurrents were always present, and this pair of incidents inspired a new, vigorous wave of calls to ban the transportation of workers on lorries, by many organisations and the public. Alternatively, workers should be transported on buses, the campaigners say. This was answered by a counter-petition from business groups, supported by the government, who repeated the concerns over rising operation costs, as well as warned the public of construction project delays and higher costs throughout society. These objections were met with heavy denunciation by the public. It is to one such criticism I am replying.

The Submission 📤🗞️

I refer to the letter, “Firms had time to plan for a ban on lorries ferrying workers” (Aug 4).

The writer holds that, “If society at large thinks that migrant workers should be transported in a safe way that is respectful of their human dignity, that is what should be made to happen.” His efforts in championing the causes of a marginalised group are laudable, but he frames the issue misleadingly.

Considered in isolation, it is unquestionable that people feel we should improve migrant workers’ safety and dignity. Who doesn’t? But that’s not the issue. The contention is whether the benefits of the improvements outweigh the costs.

I believe we should minimise road casualties (if it can be achieved at no cost), but I do not think the speed limit of highways should be halved. Implicit in the lack of objections over prevailing speed limits, society agrees that safety can be traded off for economic productivity to a certain extent.

The writer also contends that without the goal of “banning the use of lorries for transporting workers”, “little will change”. That is not right. The quality of migrant workers’ conditions in Singapore will advance if, among other things, the economic conditions of their home countries or the quality of employment the workers can find elsewhere improve.

Of course, a society is not ineluctably consigned to accepting the outcomes of market forces. We can transcend the dictates of the market to uplift a deprived and underrepresented group. One may even argue that the current treatment of migrant workers has the negative externality of damaging Singapore’s international reputation, for example. This gives us market-based reasons in addition to virtuous reasons for ameliorating migrant worker welfare.

Furthermore, we need to consider the unintended consequences of improving worker safety. We should not discount the government and businesses’ concerns over cost feasibility, which must be heeded in order to mitigate resultant unemployment among migrant workers. Moreover, we cannot understate how integral migrant workers are to our economy and hence the project delays and higher costs regulations may bring. This is not some callous commercial calculus—it is a well-intentioned endeavour to seek the optimal compromise and work out an apposite scheme of implementation (i.e. the so-called timeline).

Nonetheless, that many Singaporean consumers are willing to endure significant economic repercussions is indicative of their emphatic resolve to see migrant workers being treated better. Hopefully, our society can reach a solution that takes into account the inputs of various stakeholders.

Comments ⌨️

I looked up the name of the article’s writer, John Gee. He’s an activist of migrant workers’ rights in Singapore, and was the president of the NGO Transient Workers Count Too (TWC2).

This submission is similar to a previous one on restaurant water pricing, in that both were replies to a notable member of society and are among my more controversial writings. That also did not get published.

There is an idea I thought of but did not submit, due to my being unsure and having exceeded the word limit. Improving the conditions of these migrant workers would attract more people to work similar jobs, competing away the safety improvements via regressions in wages or lower rates of increase in wages or in other strands of the overall employment condition. Such an effect would be facilitated by low barriers to entry of becoming a migrant worker and low barriers to hiring migrant workers. So we run the risk of overestimating the benefits of making workers safer on lorries.

Would this be the case? What other elements may this result be premised on?

A Critique Of Prevalent Sentiment

Thoughts on the respective top-rated comments of two posts on a popular online site. The commenters criticise the government’s hesitation and hence perceived lack of concern for migrant workers’ safety.

Comment 1: Because we are pro-business country and business concerns will always come first before ethical concerns.

Paraphrased: Because we are a pro-business country and business concerns will always come before ethical concerns.

Comment 2: People injured or die acceptable.. profits take a hit unacceptable

Paraphrased: People getting injured or dying is acceptable while profits taking a hit is unacceptable

Such ways of thinking, which dominate the public perception, are unsound and misleading.

On Comment 1:

It does not make sense to interpret the “business sphere” and the “ethical sphere” as having an ordinal relationship, that is, as one ranked above the other, exhibiting a distinct hierarchy.

Suppose a companion and I have a choice between 2 restaurants. Restaurant A with better and more expensive food, and Restaurant B with inferior and cheaper food. I choose Restaurant B. Would it make sense if my counterpart were to assert consequently, “you are pro-money person and money will always come first before culinary concerns”? Oh no, Restaurant B has closed down, and been replaced by Restaurant C, which also has inferior and cheaper food than Restaurant A. Now, between a choice of A or C, I prefer A. Have I, almost instantaneously, become a “pro-culinary person”, and that for me, “culinary concerns will always come first before budgetary concerns”?

Suppose you left your home, and en route to your destination wonder if you locked your door. If you decide not to turn back to check, would this imply that you are a pro-convenience person, for whom convenience concerns “always come first before” security concerns? No, it does not make sense to generalise like this. There are other factors, like the distance from home, the cost of being on a derailed time schedule,, the uncertainty over whether the door was locked, and how often your neighbours get their houses ransacked. Had any of them been different, you could have made a different choice. In a different scenario where the tradeoff is also between convenience and security, you could have made the opposite sacrifice.

If I jaywalk instead of walking 100m to the nearest overhead bridge, would this imply I believe convenience comes before safety? If the government does not forcibly impose vaccines upon its population, would it imply the government believes liberty comes before health? If a parent allows his/her child to frolic at the playground, would that imply that the parent routinely prioritises fun and child-development over the painful risk of grazed knees and knocks to the head? No, I just believe the utility from that particular convenience makes the marginal cost to safety worth it. If there were a zebra crossing 20m away, maybe I would discard the idea of jaywalking, as the utility I gain from jaywalking may have fallen below that of the marginal cost to safety. Similarly the government believes the benefit from that particular instance of respecting personal choice outweighs the marginal cost to public health. The loving parent believes the utility to the child’s well-being from that particular occasion of play warrants the marginal cost of danger.

The lesson is that agents make decisions on the margin. So any model that imposes a categorical decision approach is a very poor model. The formal solution to the Diamond-Water paradox is the concept of marginal utility.

Budget, food quality, convenience, punctuality, security, safety, liberty, public health and fun are all important, and it does not make sense to declare a ranking amongst them. We care about each of these broad dimensions, and assign normative values to aspects falling under these dimensions, specific to the situation in question. A bit of introspection suffices to reveal that decision-making entities never really rank such dimensions ordinally. Do coal miners care about their safety? Of course they do, and they also care about making a living. Different people are willing to accept different levels of compensation for certain degrees of danger, which reveals how they judge and weigh different considerations. A coal miner for instance may be willing to accept $500 for a 1 in 15,000 increase in the chance of death. But it makes no sense at all to thus declare that coal miners are people who view financial concerns as more important than safety concerns. That same coal miner probably will not be willing to accept $500 for a 1 in 150 increase in the chance of death. We do not now change tack and say that, for coal miners, safety concerns are preponderant over financial concerns.

I plan a future post pursuing this problem further, which I provisionally term the Fallacy of Ordinal Importance. But we have to return to the context in which Comment 1 was made. Some “business” factors are deemed more pre-eminent than “ethical” considerations, and vice versa. On banning the transport of people at the back of lorries, we may deem that the cost of lost lives outweighs the benefits of preserving employment. Simultaneously we may judge that the benefits of economic productivity outweigh the costs of traffic injuries. A possible upshot of such an evaluation could be that we decide not to ban back-of-lorry transport. How we value each cost and benefit is a function of the empirical particulars of the problem. There is nothing in the underlying decision-making that generalises considerations of one “broad sphere”—the “business” or the “ethical” sphere—as dominant over another. If a certain empirical measure changes, we could reach a different final result. For example if the danger of travelling at the back of lorries surges exogenously, we would expect that regulators would be less tentative over new safety requirements, and that those laws would be more likely passed. That’s not because safety concerns have all of a sudden “came first” among other considerations. It’s because the parameters of the problem have changed.

Furthermore, placing “broad spheres” in a pecking order does not make sense, not least because the bounds of the “spheres” are nebulous. Not even considering other so-called “spheres”, the partition between only the business and ethical spheres is not evident, making a completely disparate treatment of these twin spheres problematic. In which sphere do we categorise a company’s Corporate Social Responsibility efforts? And if it is to be shared among the 2 spheres, in what ratio? Or should we consider the business and ethical spheres as overlapping? If so, there is no business-ethics dichotomy. Recognise that there is nothing in the ontology of empirical parameters that necessarily define them as being a “business” or “ethical” aspect. What we term as a “business concern”, “ethical concern”, “social concern”, “economic concern”, “environmental concern” et cetera is a matter of human convention. Yet, for most items, humans agree on which “aspect” it belongs to. This is not evidence of the transcendental objectivity of these “spheres”. It just shows how humans are influenced by our common socialisation, educaton and cognitive wiring (genes).

Lest there be misunderstanding, in many cases referring to business and ethical spheres in everyday language is still useful, if not essential for communication. Clear communication involves trading off precision for digestibility and expediency. But in this scenario Comment 1 conveys a completely false way to think about the issue.

On Comment 2: Both human casualties and dampened profits (provisionally disregarding distributional consequences) are undesirable, hence both, considered independently, are unacceptable. But the independence condition does not hold, so, as is the case for any general tradeoff, there is a point where the balance between the 2 undesirables is deemed optimal, and that balance occurs at a point where both undesirables are at some positive amount. That is, the optimal levels of danger and thus casualties are not zero.

The point of optimality reveals the relative degrees of unacceptability of the undesirables. If indeed one aspect of the tradeoff were not deemed unacceptable at all, a tradeoff would not exist to begin with. That is, if, as Commentor 2 derisorily implies, the government believes dampened profits are unacceptable while traffic casualties are acceptable, there is simply no tradeoff. Clearly both are unacceptable, and the government concurs. Hence Comment 2 is attacking a very weak straw man.

People must in many cases subdue their tendency to pigeonhole properties in dichotomous categories. Instead, we should conceptualise qualities like “acceptability” as a continuous spectrum of different extents.

Coda

Maybe we can think about why migrant workers’ issues have in particular caught the attention of many locals. Because people have compassion. Yeah, but there are millions more people who live more miserable lives whom we barely ever think about as the water runs from our taps. Thus the presence of dedicated compassion to one group of people is not really so self-evident. Setting out reasons for why there is compartmentalised compassion is not a vain or insensitive exercise.

First is the direct visual impact due to the sheer ubiquity of such workers in the immediate surroundings. During the day when they are working, it is virtually impossible to miss sight of them when one heads outside, as they are present in practically all construction and maintenance sites, of which Singapore has a high concentration. Second, these workers are easily identifiable by their different appearance, behaviour and culture. Last is the palpable discomfort of feeling the unfairness of life. The most expensive cars in the world flow along roads that are sporadically dotted by those lorries, carrying workers to their next 8-hour shift engulfed in harsh tropical elements. Such lorries are very noticeable and the contrast constantly stimulates locals’ conscience and sympathy by reminding them of their fortune (I have a leather seat with air-conditioning and they don’t). It reminds people: That could have been me. It was only the luck of the draw placing us in profoundly diverging life circumstances. Phenomena that are more visible and shocking to the senses tend to capture a larger share of the public consciousness.

The Price Of Life 🔖⛑️🧮

The part of my article that probably is the most controversial is the paragraph on speed limits. In that section, I implicitly make an accusation of hypocrisy or at least an internally conflicting position, and made explicit the notion that we tradeoff human lives routinely, thus insinuating the often-offensive idea that life has a finite worth. But surely it is worthwhile to lose at least one life per day globally to traffic mishaps if it means the whole world gets to drive twice as fast1.

Many people, when talking about issues related to human safety, opine that “you cannot put a price on human life”. (Whether this comes from honest ignorance or a propensity for virtue signalling is speculative, but only the former motive deserves consideration.) A great number of such objectors are of reasonable intelligence as demonstrated by achievement in other fields, but in the case of placing a finite value on human life, their perspicacity fails them. An explanation most likely is that their acuity is impaired by their sentimental repugnance to such a notion. It would be harsh to reproach a layperson for this fault. Nonetheless antipathy cannot be a valid remonstrance. During most of humans’ evolution, life was so precarious and social groups so small it was often more expedient, useful and even sufficient to think of the maximisation of existential safety as the sole and pre-eminent guiding principle of action. And espousing heretical ideas about safety in those times was probably a poor signal of sociability. Humans are good learners, but fundamentally they did not evolve to intuitively conceptualise the accounting of the aggregate effects of decisions affecting populations that far exceed Dunbar’s number.

What’s despicable about the assertion “you cannot put a price on human life” is that people who propound this notion do not demonstrate behaviour consistent with their belief. Do you wear a helmet and mask everywhere you go? Why don’t you wear a more protective helmet and mask? Why don’t you contribute to developing more protective ones? Would you be willing to give up all your material possessions to reduce your chance of dying now by 1-billionth of a percent? (These questions seem absurd, but they are mere corollaries of the principle that life is infinitely valuable.) Why are your answers to all these questions non-affirmative? Because life is not infinitely valuable—to you life has some finite worth relative to the quality of your existence. You value life and the things in life finitely, and along a common underlying dimension—that’s why you’re willing to take on a higher probability of death for improved life quality. Individual heterogeneity in normative opinions is permissible, but incongruity, as in an internally incoherent system of belief and action, is abhorrent.

In addition, dissidents of life-pricing overlook basic observations about society’s distribution of resources and government decisions. Why do governments spend at all on Christmas decorations? There is always more pathogen research to be done and fire safety equipment to be augmented. Why don’t governments outlaw coughing and sneezing in public? Even if they do, why not raise the punishment and expand enforcement? Why don’t governments squeeze money out of their middle-classes (upper-classes can take flight easily) to uplift those of high starvation-risk? You may argue that it’s because such “extreme” measures are politically unpopular. Well, these would be very politically palatable if people genuinely believed life is infinitely valuable. People don’t, which is also why these measures are deemed radical in the first place.

It seems opportune at this stage to include in our discourse the ‘value of a statistical life’ (VSL). It is a well-known metric used in regulators’ cost-benefit analysis. Remember the coal miner who was willing to accept $500 for a 1 in 15,000 increase in the chance of death? Through controlling for relevant variables, and across a large sample of workers of varied industries, the isolated correlation between extra remuneration and risk can be discovered. For example, people may on average earn $500 more for taking on a 1 in 15,000 higher risk of dying due to their job. The VSL is thus $7.5 million ($500 x 15000). Note the criticality of the word “statistical”. VSL does not apply to deciding whether to rescue identified lives, or specific individual lives. VSL exists to help us make informed choices on tradeoffs, by allowing us to determine if a policy passes the cost-benefit test. VSL has positive income elasticity—it tends to be higher in wealthier countries. Statistical lives are normal goods, likely even luxury goods.

This is blasphemous! VSL is a heartless concept used only by third-rate governing bodies. This sentiment cannot be further from the truth. VSL is inherent in all countries and jurisdictions, because it is implied in their policy choices. It is even explicitly acknowledged by some American government agencies, for example. Of course, these information do not justify the pricing of life, but it dispels the notion that the price of life is an irrelevant concept detached from how a modern state decides how to allocate scarce resources.

VSL is not some vile relic of a primitive era, that would be unthinkably barbarous in our day. Such an abstraction is central to both the enactment and calibration of policy especially because governments’ ability to dictate the fates of its populace are so expansive. This holds true regardless of a state’s degree of autocracy. For instance in the COVID pandemic, governments had to know the value of preventing a certain number of deaths, in order to determine things like whether to mandate mask-wearing, when to make it optional, the duration and extent of lockdowns and other social distancing practices, how strictly these laws are to be enforced, how much to spend on vaccines, how to implement immunisation programs, how much or whether people should pay for vaccines et cetera. If policy choice and calibration are not to be arbitrary (yeah, “arbitrary” is admittedly a straw man, but you get what I mean), but based on deliberate calculation, valuing statistical lives is inevitable. Surely the latter is more desirable. Human life, as treated by a policymaker, is but one variable among multiple others. Is this practice stone-hearted?

In a later paragraph I contend that the consideration of business and economic ramifications is “not some callous commercial calculus—it is a well-intentioned endeavour to seek the optimal compromise and work out an apposite scheme of implementation.” I reckon that from some dogmatic quarters there would still be expostulation against this proposition, even as I built my argument up with that digression on speed limits, which could have sowed some anticipation in the reader of what is to ensue.

The heed of economic consequences is not callous. There is a case to be made for cold-bloodedness only when economic interest is weighed in overwhelming favour of workers’ safety. Of course, what “overwhelming” entails is ambiguous. At which point the relative weightage starts to become unconscionable is normative. But in general, the assignment of a positive weight to any aspect of a tradeoff that has human life as one of its strands is not callous. Only by pricing life do we have a coherently justified route to, for example, avoiding financial ruin for a whole nation for the sake of rescuing a mere dozen lives. Life is important, and so is its quality. That’s why policymakers price them. This allows both life and the things in life to be given consideration.

One may be uncomfortable with that lives are denominated in currency units, as is the typical practice. A common unit is indispensable—how can a regulator compare things of such different character, like lives and lost jobs? We can’t claim that 5 Joules is a larger quantity than 3 picofarads. We can only compare things in the same dimension, so we must denominate them in the same unit through some method of conversion, such as the revealed preference approach in the case of VSL. But any difference in the choice of unit is purely a matter of expediency and preference. Value is usually quoted in currency units as it is the most common and relatable medium of exchange. You could use as the denomination broccoli, bow ties, roller skates, Kindles, spatulas or bald eagles. The common dimension is the point—not the choice of unit.

Belabouring 🦜🗟

I have to over-elaborate: It is not that the self-perceived gods of the economics discipline are telling the rest of us mortals what the value of life should be. Instead, it is describing how much we value life, based on our real decisions. Obtaining an explicit value helps because it is not so obvious how decisions should be calibrated among conflicting goals. After producing an explicit value, we can derive the implications of that particular value. The goal is to better align decisions with optimising human welfare. (How honourable an endeavour!) Lastly, whether to prescribe what models suggest is normative, which is beyond the domain of the subject.

A Critical Objection ⚠️

Now we encounter a complex challenge to our argument. It is so far the most intractable, but ultimately not insuperable. Tackle it we must, for otherwise it remains dormant. Why I describe it as such, and why I have found it necessary to treat, is because it seems inevitable this counter-argument would emerge in the mind of any person who has devoted some rumination on this issue.

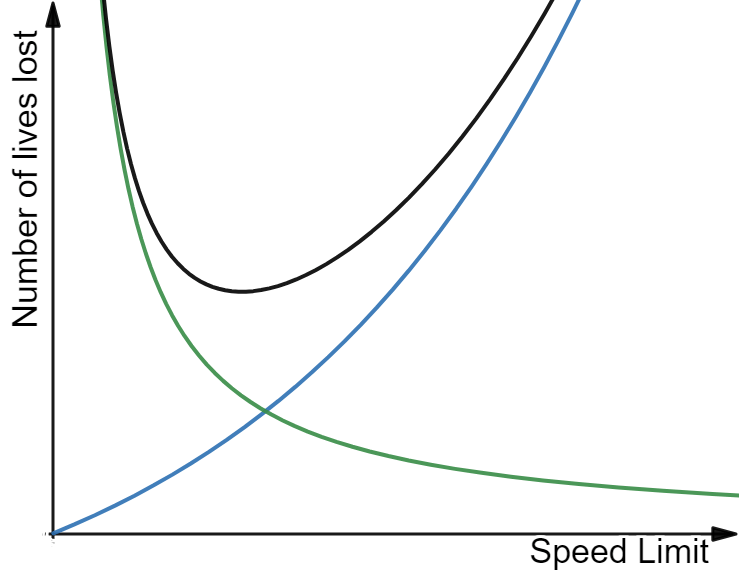

So the objection goes that, yes, lowering speed limits decreases the number of lives lost to traffic accidents, which for expediency we call Effect A. However, reducing speed limits, via dampened economic productivity, increases the number of lives lost to speed limit-induced destitution. This we call Effect B. These 2 effects are contrasting—for all possible values of the speed limit, they change in opposite directions as the speed limit varies. As Effect A and B are opposing, there is a point where aggregate lives lost is minimised, and that indicates where the optimal speed limits may reside.

We must note the implications if the above were true. Such an explanation, for it to sufficiently hold, does not require the consideration of the other aspects besides human life itself. It would mean that, in this specific instance of speed limits at least, policy calibration is based on “lives saved” as the sole guiding measure. This, if we cannot repudiate, can be seen as a significant blow to our position, that both existential and the other aspects of living are considered in the same dimension, with some positive finite weight.

The following is how we may represent what we have so far considered in this section. This brief technical detour is not done for its own sake, but to aid conceptualisation.

Graph of the Number of Lives Lost against the Prevailing Speed Limit

Green / Downward Sloping: Effect B—Number of lives lost to speed limit-induced destitution

Black / Concave Upward: (Effect A + Effect B)—Total lives lost

Effects A and B are represented by concave-shaped graphs as diminishing marginal benefit is assumed. Supporting this presumption for Effect A is that kinetic energy is proportional to the square of the speed (outpaces linear growth).

Let y = Number of lives lost

Let x = Prevailing speed limit

BLUE: ya = A(x)

GREEN: yb = B(x)

BLACK: ytotal = A(x) + B(x)

Let the speed limit at which the number of lives lost is minimised be x*.

x* is the value of x at the minimum point of the black curve.

Condition C: ytotal is minimised, so policymakers target x = x*

Recall that the validity of the above challenge rests on the veracity of Condition C. Even if it may hold in poor regions of the world, in many wealthier societies there is likely to be significant allowance for lowering speed limits and reducing overall lives lost, that is, Condition C does not hold. Maybe in a country like Singapore (2nd-highest GDP (PPP) per capita), a road safety regulation like banning motorcycles on expressways, or reducing their speed limit on highways, would result in positive net lives saved2. Germany’s autobahn is famous for being loose in its speed regulations. Current speed limits are what they are because we recognise the pleasure derived from faster travel, and the utility of non-existential economic benefits. Furthermore, this model predicts that speed limits would decrease frequently by small increments as the number of people living close to existential immiseration falls, yet this is not observed.

Practically speaking, it is hard to conceive of a policymaker making Condition C the sole basis of calibration. Effect B is impossible to measure precisely. There are just too many economic variables, and too much noise and information! Given that information is imperfect, a policymaker would err on the side of x > x* rather than x < x*, because there are many non-existential benefits to x > x*, but not for x < x*. We would expect that most, if not all, jurisdictions employ x > x*.

Final Remarks 🏁

Economics is sometimes often viewed as a cold-blooded discipline. These psychopaths are always obsessed with placing numbers on wonderful things like the joy of ice-creams. How can my “free” decisions be described by these abstruse models? I am unique, and while I get nudged by external influences, I nonetheless retain a permanent, metaphysical soul impervious to outside forces. (Aw man, not people believing in free will again.) Many people are alienated by economics, and suspicious of economists. The subject suffers a bad name both in many circles. Multiple studies3 famously allege that people who study economics tend to be more unsympathetic. This is conceivably due to certain perceived implications of the methodology of economics.

Perhaps one could opine that there is no obligation to appreciate migrant workers’ efforts, because, in choosing to work in another country, they are merely undertaking an activity which they deem improves their welfare, and which they judge the most optimal use of their time. It is not from the benevolence of the workman, the labourer, or the operator, that we expect our manpower, but from their regard to their own interest.

We can take this to be true in a framework of self-interest, which has robust explanatory power. However, contrary to what some may believe, this way of thinking about human action does not impede, much less preclude gratitude. Why parents suckle their young and raise their children can be explained using a self-interested framework, but we still feel strongly indebted to our parents, and there is nothing in the framework of self-interest that objects to, or discounts appreciating them, nor can it be thus deemed wrong to do so.

Models involving self-interested agents, no matter how narrow the interpretation of self-interest, or any positive model, do not bear any implication on how one should act, because positive descriptions cannot entail normative prescriptions (Hume’s fork). This is not a technical shortcoming we can conquer with better or alternative models, but a transcendental one that holds immutably.

Humans routinely “derive” ought from is, without realising that their normative assertions necessarily and without exception emanated from an implicit moral code. Counterintuitive this may be, due to how ingrained and natural our moral instincts are. Our thinking relies greatly on heuristics, including assumptions. Usually, the more fundamental the moral instinct the more difficult it may be for someone to accept the principle, as people feel a more intense aversion towards the corollaries of the principle.

That morality is decreed not by transcendental, but by worldly fiat can be unsettling to both the rulers and the ruled. Hence seeking ethical rules with transcendental justifications has been a human endeavour for millennia. It is curious to note how humans tend to be very antipathetic to a moral system based purely on human convention, as if those “transcendental moral principles” were not a function of human attributes anyway.

People believe in fiat money while being cognisant of its fiat nature, but are unable to do the same for fiat morality. This may be because the former is viewed as a facilitator of human activity while the latter a foundation. Though moral codes are really only facilitators too.

At last, no matter how the conditions of migrant workers develop amidst the multi-stakeholder tug-of-war, we need to respect, admire and value the exceptional and indispensable work they do 🫡

Reflections 📔

This post took a month to complete, and much, much more time than expected to think and write about. It was conceptually difficult to navigate, though many of the convictions espoused I have held for a long time. What hampered progress and troubled me greatly was also the controversial things I propound.

Further Resources 🗃️

- A very nice website championing migrant workers’ welfare

Footnotes 📝

1: Around 1.3 million people die in traffic accidents per year, according to the WHO. That’s an average of >3000 deaths a day.

2: Indeed Singapore has ~2.0 road accident fatalities per 100,000 people per year, while its starvation rate is practically zero. Of this practically zero incidence of starvation, an even smaller component is caused by speed-limit induced destitution.

3: Dorling (2021) says, “There are many studies now that show how university students of economics find moral behaviour unusually difficult to understand, and that less morally inhibited students perform better in learning the subject, or at least the subject as it is currently taught in the USA and UK. This has now been clear for more than three decades. It has become routine to point out that economist[s] tend to lack morals and compassion [at] least once every ten years (Frank et al., 1993; Zsolnai, 2003; Ward Perkins and Earle, 2013), and yet little is done to address the problem.” This sounds pretty loaded, yet it is not unrepresentative of a significant proportion of views on this issue.

Extra: AI Response

On the question of “Should policymakers place a price on human life?”, this is what my website builder’s AI had to say:

“Policymakers often grapple with the difficult task of weighing the value of human life against other considerations. While it may seem morally uncomfortable to assign a price to human life, there are practical reasons why policymakers engage in such assessments.

The concept of valuing life, often referred to as the “value of a statistical life” (VSL), is utilized in cost-benefit analysis to aid decision-making. This metric helps policymakers determine if a particular policy or intervention is cost-effective by comparing the expected benefits, including lives saved or injuries prevented, to the associated costs.

It is important to note that assigning a value to human life does not mean that life is inherently replaceable or expendable. Rather, it recognizes the reality that resources are limited, and policy decisions must be made with the aim of maximizing overall societal well-being.

By considering the potential costs and benefits of different policies, policymakers can make informed choices that optimize outcomes and allocate resources effectively. This practice allows them to weigh the value of human life alongside other pressing concerns, such as economic productivity, public health, and social welfare.

Ultimately, the goal is to strike a balance between preserving and enhancing human life while also addressing the myriad complexities and trade-offs inherent in policy decision-making. It is a challenging task that requires thoughtful analysis and consideration of various factors, including ethical, economic, and practical considerations.”

Wow AI is alarmingly good.

2 thoughts on “On The Conveyance Of Migrant Workers 👷”