Contents List

- Preface

- Context

- The Submission 📩

- The Edited Letter 📧

- The Published Letter 📰

- Extension Ⅰ: 🇮🇱🚸

- Extension Ⅱ: 🤑💰

- What It Looks Like In Print 🖨️

- A Realisation

- Thoughts

- The Final Problem

- Footnotes

- Reflections On This Post ✍️

Preface

I submitted a letter to the Straits Times Forum upon reading this letter, which condemned hawkers for imposing charges on plastic bags and disposable utensils, amidst considerable online chatter on this issue.

Context

On 3 July 2023, a disposable carrier bag charge of at least 5 cents was mandated for all major supermarkets in Singapore. It is a minimum price (price floor) to correct the negative externalities of plastic bags.

It took no more than 2 weeks for the media and many netizens to catch on to news of some hawkers charging individual prices for plastic bags and disposable cutlery.

The text on the paper below reads:

Everyone has a duty in supporting environmental protection!

Takeaway $0.30

Plastic bag $0.10

Cutlery $0.10

(“Takeaway” refers to single-use takeaway containers (styrofoam or plastic). “Cutlery” refers to disposable utensils, which are usually plastic spoons, plastic forks and wooden chopsticks. Presumably, the charges for “Plastic bag” and “Cutlery” are per unit. The charge for “Takeaway” could be per unit or per transaction.)

The Submission 📩

I refer to “Some hawkers charging for disposable utensils and plastic bags” (18 July).

The writer believes that recent rises in hawker prices already account for the costs of plastic bags. He has overlooked the shift in market conditions brought about by the recent mandatory plastic bag charge in major supermarkets.

If alcohol is taxed at supermarkets but not at 7-11, consumers will shift their alcohol purchases to 7-11. As plastic bags from major supermarkets have become more expensive, demand for plastic bags from other sources has increased. Consumers demanding more plastic bags from hawker stalls is a predictable and perceptible consequence of the minimum 5-cent charge. It is reasonable for hawkers to take targeted measures in response, especially with how price-sensitive many consumers are to plastic bags.

Furthermore, the writer contends that “It would seem unjustifiable for hawkers to charge more for these items on top of the price of the food.” Hawkers could absorb the increased cost of supplying more plastic bags into food prices. But that would undercharge people who unabashedly take a lot of plastic bags, and overpenalise people who do not take plastic bags. Perhaps it is preferable for people to pay according to individual consumption.

The writer also asserts “The general public cannot always be expected to absorb extra fees in the name of the green initiative.” For a given state of technology, improving environmental outcomes always entails monetary or lifestyle trade-offs incurred by the population. That’s why saving the environment is so difficult in the first place. It is not a free lunch. Collectively, we should start getting used to accepting the negative financial or quality-of-life impacts addressing environmental concerns will bring.

Comments

It is interesting to see the operations of the market manifest. Prices of plastic bags in supermarkets rise, causing the demand for plastic bags in hawker stalls (a close substitute) to rise, which creates upward pressure on its price.

Hardly any news or comments alluded to the recently imposed plastic bag charge in supermarkets. Some refer vaguely to “cost pressures”, which is very lazy and uninformative because it has been ongoing for at least a year now and regurgitated ad nauseam by everyone. On the other hand, cynical keyboard warriors accuse hawkers of “profiteering”. I don’t see how a stall that clearly displays all its prices and operates in a hawker centre with dozens of competitors can fleece its customers.

When governments tax cigarettes, they usually do not only tax cigarettes sold by 7-11. It is worth trying to understand why the Singapore government did not impose the plastic bag price floor on all retailers, but only on major supermarkets. Non-major-supermarket retailers suffer from the partial price floor, as their costs increase due to higher plastic bag acquisition by customers, yet if they adjust their pricing policies in response, they receive flak.

Rather than merely refashioning infographics on hackneyed suggestions like saving water or reducing food waste, the government should give more focus to educating citizens on the notion that they will bear monetary and lifestyle tradeoffs in the process of ameliorating environmental problems.

The Edited Letter 📧

(The Forum Administrator replied my email with the letter which incorporated the Editor’s changes. In strikethrough and yellow are the edits with respect to my original submission.)

I refer to the letter “Some hawkers charging for disposable utensils and plastic bags” (July 18).

The writer believes that recent rises the rise in hawker prices already accounts for the cost of plastic bags. He has overlooked the shift in market conditions brought about by the recent mandatory plastic bag charge in major supermarkets.

If alcohol is taxed at supermarkets but not at 7-11, consumers will shift their alcohol purchases to 7-11. As plastic bags from major supermarkets have become more expensive, demand for plastic bags from other sources has increased. Consumers demanding more plastic bags from hawker stalls is a predictable and perceptible consequence of the minimum 5-cent charge.

It is reasonable for hawkers to take targeted measures in response, especially with how price-sensitive many consumers are to plastic bags.

Furthermore, the writer contends that said: “It would seem unjustifiable for hawkers to charge more for these items on top of the price of the food.” Hawkers could absorb the increased cost of supplying more plastic bags into food prices, but that would undercharge people who unabashedly take a lot of plastic bags, and over–penalise people who do not take plastic bags. Perhaps it is preferable for people to pay according to individual consumption.

The writer also asserts said: “The general public cannot always be expected to absorb extra fees in the name of the green initiative.”

For a given state of technology, Improving environmental outcomes always entails monetary or lifestyle trade-offs incurred by the population. That’s why saving the environment is so difficult in the first place. It is not a free lunch.

Collectively, we should start getting used to accepting the inevitable negative financial or quality-of-life impacts addressing environmental concerns will bring as we address environmental concerns.

Comments

Removing the word “more” here is very dubious. I’m sure there are many people who do not consider the plastic bags expensive at its current price.

Moreover, the editors truncated “For a given state of technology”. I am quite dismayed by this edit. This contingent phrase is essential and removing it could set me up for criticism. Though one could argue that improving technology also incurs costs due to the resources required for research, I feel it is safer and more thorough to qualify with “For a given state of technology”. This would offset the absoluteness of my sentence.

The Published Letter 📰

(In strikethrough and yellow are the edits with respect to the edited letter.)

Time to accept trade-offs of pursuing green initiatives

I refer to the letter “Some hawkers charging for disposable utensils and plastic bags” (July 18).

The writer believes that the rise in hawker prices already accounts for the cost of plastic bags. He has overlooked the shift in market conditions brought about by the recent mandatory plastic bag charge in major supermarkets.

As plastic bags from major supermarkets have become expensive are no longer free, demand for plastic such bags from other sources has increased. Consumers demanding more plastic bags from hawker stalls is a predictable and perceptible consequence of the minimum 5-cent charge by supermarkets.

It is thus reasonable for hawkers to take targeted measures in response, especially with how price-sensitive many consumers are to plastic bags.

Furthermore, The writer also said: “It would seem unjustifiable for hawkers to charge more for these items on top of the price of the food.” Hawkers could absorb pass on the increased cost of supplying more plastic bags into in the form of higher food prices, but that would undercharge people who unabashedly take a lot of plastic bags, and over-penalise people those who do not take any. Perhaps it is preferable for people to pay according to individual consumption.

The writer also said added: “The public cannot always be expected to absorb extra fees in the name of the green initiative.”

Improving environmental outcomes always entails monetary or lifestyle trade-offs incurred by the population. That’s That is why saving the environment is so difficult in the first place. It is not a free lunch.

Collectively, we should start getting used to accepting the inevitable negative financial or quality-of-life impacts as we address environmental concerns.

Comments

I am not so pleased with the published version.

Let’s start with the article title they gave. “Time to accept trade-offs of pursuing green initiatives”. This is hardly what I envisioned.

My article is primarily a defence of the hawkers’ pricing policies, not an environmental appeal. My last rebuttal to the writer is an auxiliary point, secondary in primacy. It was added because my letter felt short and I couldn’t expand my discussion on hawkers any further. Also, as my article is a rejoinder to another writer’s letter, including that last point makes my reply more comprehensive.

I at least expected the word “hawker” to be in the title. I imagined something along the lines of “Reasonable for hawkers to charge for plastic bags and disposable utensils”. But I understand why the Straits Times conferred that title, as it elevates my article to be about a wider point, making it more impactful and attention-grabbing. I gradually grew to find the title they gave more agreeable and apposite.

I am not tolerant of the following 2 edits, however, as they removed 2 vital qualifications which had the effect of defiling the main points.

Firstly, “perceptible” was a last-minute addition to the original submission as I realised the nuance provided by this additional adjective is essential. One may expostulate with my argument (as people like to do when they catch a “perfect information” assumption) by rebutting that hawkers do not have complete knowledge of market influences and their magnitudes, so they cannot make projections in the first place. Thus, being “predictable” alone does not sufficiently justify the hawkers’ newly-imposed charges.

But although some hawkers may adjust prices according to the knowledge that plastic bags in major supermarkets have been subject to a price floor, awareness of that is not necessary to compel hawkers to make price adjustments, as long as they discern a rise in demand based on their first-hand interactions with customers. Hence the criticality of the word “perceptible”.

Secondly, the intention of this clause (“incurred by the population”) is to make the response to the writer clearer and more direct. There would be inevitable monetary trade-offs, and they would be borne by the people. The writer in his original article possibly implied that he believes governments or corporations should endure the costs without passing them on to the public.

Under a variety of constraints, newspapers have to make sure everything fits nicely. However, they could have cut the portion “in the first place. It is not a free lunch.” because it adds colour but no substance.

I also do not like that they used “no longer free” to describe the cost of plastic bags at supermarkets now. I tend to eschew the word “free” because there is always a cost to something. Furthermore, for a decade since 2007, NTUC (Singapore’s largest supermarket retailer) gave a 10-cent rebate to customers who brought their own bags. That scheme was then supplanted by a program which charged a fixed amount for any transaction that uses at least 1 plastic bag4 (at selected stores). Clearly, “no longer free” isn’t the most accurate way to call the plastic bags now.

Extension Ⅰ: 🇮🇱🚸

This is a Reddit thread on the issue. A couple of noteworthy comments in there.

Comments

Person 1: vaguely remember there was a case at a daycare where they started charging parents for late pickups and it only resulted in more late pickups

Person 2: That study just showed that when there’s a penalty, some people will view it as a charge and factor it into their expenses. In this case it’s already a charge for the container/bag/whatever so it won’t make much difference.

Person 3: How would that apply here? Get charged for takeaway results in me buying more food?

Person 4: The actual case was that since parents are already being charged for being late, they don’t need to rush to pick up and can take their time, resulting in them picking up the kids later and teachers going home later. In this case, probably can mean since you alr getting charged for utensils, just take more lor

My Response

Person 1:

The “case at a daycare” is a famous, widely cited study in both research and popular non-fiction to elucidate the nature of incentives. It’s a memorable example of motivation crowding. The experiment was performed on multiple childcares in Israel, where parents were sometimes late to pick up their kids. Some childcares were randomly selected, and a small financial penalty was imposed on late parents.

The reason why this experiment is so famous is because the outcome went contrary to the conventional expectation then and made views on incentives less coldly classical. Tardiness rose sharply (in both frequency and degree) in the childcares which imposed fines and stayed constant in the remaining childcares which acted as controls.

Person 2:

In the context of the Israel childcare experiment it is absolutely critical to specify that the penalty imposed is a monetary penalty. To fail to stipulate the nature of the penalty marks an insufficient appreciation of the experiment. He also did not mention the most important detail—that some of the previously-felt costs were crowded out by the fine.

There are already many costs parents bear for tardiness. What are a few of them?

- Increase in exasperation when stopped by a red light while already running late

- Embarrassment when waiting teacher makes eye contact

- Having to apologise to teacher and child

- Sense of compunction towards teacher and child

- Risk of child being viewed less favourably by teacher in the future

- [And many more]

Furthermore I am unable to fathom what Person 2 is saying in the 2nd sentence. The 1st sentence sounds muddled too.

Person 3:

Good question, I thought. Until I read the last word of his comment. The Israel childcare experiment that has been highlighted is about how a pecuniary penalty for tardiness results in more tardiness. The parallel statement would be how a pecuniary penalty for using takeaway accessories results in higher consumption of takeaway accessories.

Despite the contextually wrong predicate, Person 3’s question is worth exploring. To recapitulate, he enquired, “Get[ting] charged for takeaway results in me buying more food?”

If Hermes and Louis Vuitton started charging a separate price for their trademark bright orange shopping bags, how would consumption of their products change? Well, this is not an apt example because it is quite probable that Hermes and LV’s products are Veblen goods (i.e. have upward-sloping demand curves), so consider something else.

If 7-11 started charging a separate price for their carrier bags, would demand for their products decline? Likely yes.

Person 4:

“need” and “can” are not the right words to use. I would say, “The actual case was that since parents are already being charged a small fine for being late, they experienced an overall fall in the total cost of tardiness, so they don’t need felt a lower impetus to rush to pick up and can were thus more inclined to take their time, resulting in them picking up the kids later and teachers going home later.”

Moreover, the charge on takeaway accessories will not have an effect analogous to that of the childcares’ tardiness fine. Getting charged for takeaway accessories decreases the demand for food as the 2 goods are complements.

Whether the imposition of a monetary charge reduces a negative behaviour is dependent on the extent of the crowding out effect of the fine on compunction. In the case of the Israel childcares, you are financially compensating someone you would otherwise feel much more remorseful towards. In the case of plastic bags, the remorse you are feeling is towards the whole of humanity or even the entire ecosystem of Earth, including future generations. But you only directly compensate the retailer (e.g. the hawker), so virtually none of the remorse gets neutralised.

The monetary penalty changed the nature of how parents perceive their tardiness. Without the fine, the teacher is doing them a sacrificial service and the parents are inconveniencing the teacher. The teacher is being dutiful. With the fine, the teacher is providing a child supervision service in exchange for financial compensation. The teacher is fulfilling his/her job. Apologetic emotions are partially nullified.

As the monetary penalty increases, an additional dollar in fines effects a smaller reduction in guilt and the same increase in total cost5.

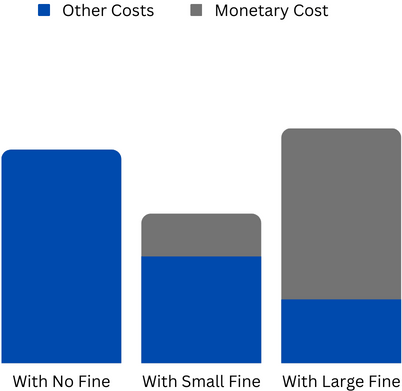

This is summarised in the bar chart below.

Graph depicting total cost under different amounts of fine

Extension Ⅱ: 🤑💰

Many netizens accused hawkers who imposed the charges of greedflation. Greedflation is a commercial practice of introducing prices rises that outpace inflation during inflationary spells, in order to increase profit margins.

Though there may be greedflation in certain industries, it is more dubious if hawkers are engaged in greedflation. Hawkers have hardly any pricing power. The cost of obtaining information to make price comparisons is very low. Even if there is greedflation, it would not be of sizeable extent.

Many businesses judge that it is better for them to raise prices considerably only occasionally, rather than make multiple minute adjustments pegged closely to the prevailing inflation rate over a period of time (to reduce menu costs and customer disgruntledness). If it is as such for the hawkers in question, then their price rises have indeed outpaced inflation, but can this still be strictly called “greedflation”?

What It Looks Like In Print 🖨️

Comments

Surprised to see they added a photo. It conveys a clear message and complements the text.

The caption, however, leaves much to be desired. It says that the writer (me) “thinks people should pay according to usage”. In contrast, my original statement was “Perhaps it is preferable for people to pay according to individual consumption.” I designed my sentence that way expressly to avoid a strong normative flavour to it. Slipshod journalism, putting words in my mouth. Poor standards of rigour.

Besides a general circumspection towards propounding normative opinions, my choice of “perhaps” was also influenced by my idea that charging for plastic bags by individual consumption worsens inequality as it may not be unsound to suppose that people with lower incomes would tend to take more plastic bags from hawkers if it didn’t have an individual price, as people with lower incomes are less willing and able to spend money on plastic bags. So, though it is nice that they appended an image to my article, their caption did me no favours by distorting my message.

A Realisation

As I observed the picture, I realised I made a grave oversight. The size of plastic bags from hawkers stalls are usually smaller than those from supermarkets and may not line the same-sized bin as closely. Thus plastic bags from hawkers may not be a complete substitute for plastic bags from supermarkets.

However, though the 2 kinds of plastic bags are not perfect substitutes, they are still fairly close substitutes as they share many functions, like packing footwear, laundry, litter on excursions, dog poop and more.

Thoughts

The hawkers’ blunder, from a business viewpoint, was their passing off the charges on takeaway accessories as an environmental initiative. Even if the hawkers were environmental zealots, it easily comes off as disingenuous. Their critical oversight was not anticipating how consumers would respond.

Reading the remarks on the Internet has bolstered my conviction that any significant progress in environmental protection can only be achieved via technological breakthrough. One of the most well-off and environmentally-aware demographics in history is losing their minds over 10 cents for a plastic bag.

The Final Problem

Should more environmental regulations be imposed?

On one hand, the potential ecological effects are so vast, catastrophic and possibly irreversible that it calls urgently for a radical lowering of the bar of policy feasibility. Maybe we should be more aggressive in pursuing environmental outcomes.

At the other extreme, a technological breakthrough that magnificently solves our problems could arrive anytime. Then we would have put people through unnecessary suffering.

You might suggest we base our current decisions on expectation and that is right, but the nature of technological breakthrough is unamenable to the assignment of probabilities we can be confident in.

And there are also the intractable systemic impediments caused by the pervasive electoral-cycle mentality and a lack of international trust and cooperation. The incentive structures of the world are poorly set up to tackle environmental problems.

My answer to “Should more environmental regulations be imposed?” is that I do not have an answer. And it is not entirely for being lazy; it is also for being circumspect on normative issues which people cannot agree upon. The answer rests on myriad normative judgements that are too far removed from the contexts in which humans evolved their moral intuitions.

Footnotes

1: A price floor on plastic bags disproportionately affect people with lower incomes as it takes up a larger proportion of their incomes.

2: In Singapore’s political context, government and ruling party are practically synonyms, and are often used and interpreted as such.

3: In view of populism’s highly negative connotation, I find it useful to disclaim that I think populism is necessarily inimical to a society’s welfare.

4: Unsurprisingly for a per-transaction charge, some customers demanded for more plastic bags than they would otherwise have without the charge.

5: For simplicity, we can take cost and the value of the fine as proportional at relatively low values of money.

Reflections On This Post ✍️

This was a much longer and time-consuming post than anticipated. There is so much that can be extended from this issue.

I think this is my longest post yet. While writing I was concerned about whether the contents of this post would be easy to follow. Is it comprehensible and coherent or too convoluted? How can the post be structured better?

One thought on “The Unreasonable Exorbitance Of Plastic Bags In The Hawker Centre 🛍️”