Read my published letter here.

(The parts the newspaper editors amended are in yellow)

The Submission

I refer to the letter, “Having fewer credit cards can make it easier to detect fraud” (June 19).

The writer believes that banks are not doing enough to deter fraudsters. But that is the point. The optimal level of fraud to society and to banks, is non-zero.

Beyond a point, further minimising the risk of fraud comes at prohibitively exorbitant costs because marginal costs rise steeply.

The costs required to completely stamp out frauds such as the US$1 his friend lost are far greater than that dollar, and those costs will be passed on to the rest of society. For instance, it will become much more cumbersome for lawful users to transact and there will be a slowdown in the economy as a whole.

Just like how the writer says that it would be impractical to “set up transaction alerts on banking apps for amounts as low as one cent”, it would be ill-considered to expect banks to eliminate fraud entirely.

As a tongue-in-cheek economist may put it, “If you’ve never missed a flight, you’re probably spending too much time in airports.”

Let me add, “If you’ve never been a victim of fraud, you’re probably not trusting people enough.”

Banks are well aware, that all else held constant, a rise in fraud will effect a fall in demand for their cards’ services. They are also the stakeholders who are most cognisant of their respective cost structures.

Banks can determine for themselves the optimal level of resources to deploy to detect fraud better than any central governing body.

As long as the banking market is kept competitive by regulators, it is unnecessary to suggest or legislate how much banks should spend tackling fraud.

Comments

They made relatively few and minor edits, only changing things like sentence structure and individual words.

I was quite surprised they published both quotes as they are counterintuitive and slightly provocative.

As I read the published letter on their website I realised the quotes could appear slightly contrived and the leap in thought flow to the quotes could be cryptic. The ideas could have been better connected. But I was concerned that adding a linking explanation would be incongruent with the tone and tempo of the rest of the letter. And I don’t want to be long-winded.

Unpacking The Quotes

“If you’ve never missed a flight, you’re probably spending too much time in airports.”

(The quote is commonly attributed to the Nobel economist George Stigler.)

(In this statement it is assumed that spending time at the airport is undesirable and has negative utility. In reality, some people enjoy being at the airport for several reasons: the airport has excellent amenities, being at the airport fuels the excitement of a holiday, having the opportunity for last-minute shopping etc.)

This may seem like an absurd proposition. Not missing enough flights?? I don’t want to miss any flights at all!

The Short, Non-Mathematical Answer

In all situations involving trade-offs, no matter how much your preference sways in a particular direction, there will never be an optimal outcome where the cost incurred on either side is zero.

The cost of minimising the cost on either side increases as the cost on that side is minimised.

The Longer, Mathematical Answer

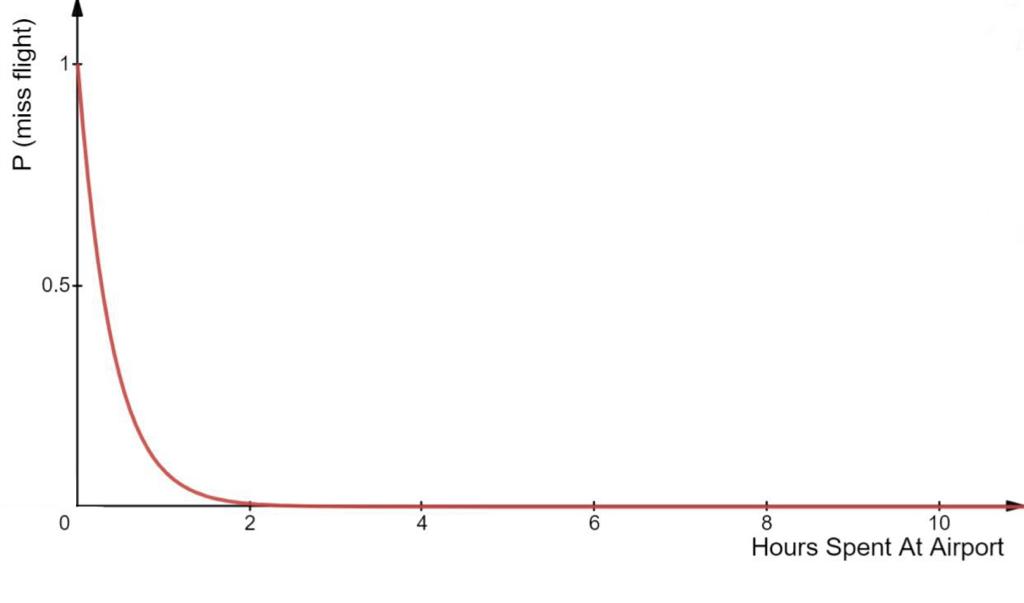

This is a graphical interpretation of the tradeoff between minimising both the risk of missing a flight and spending time at the airport.

The Trade-off Curve

Let y = P (miss flight)

Let x = Hours Spent At Airport

If you don’t go to the airport, you definitely miss your flight (i.e. when x=0, y=1), so there is a vertical intercept at (0,1).

At small values of x, y falls steeply given an incremental increase in x (i.e. the rate of change of y with respect to x is very negative). You can decrease the probability of missing your flight significantly by spending a bit more time at the airport.

As x increases, the extent to which y falls for every incremental increase in x decreases (i.e. the rate of change of y with respect to x decreases in magnitude OR the rate of change of x with respect to y is very negative). You need to sacrifice progressively larger amounts of time at the airport in order to effect the same fall in the probability of missing your flight.

y approaches 0 asymptotically as x tends to infinity. y cannot be 0 due to the nature of the probability of empirical events like missing a flight.

Based on the relative amounts of (negative) utility they associate with missing your flight and spending time at the airport, the point of optimality of different individuals who have different preferences will lie on different points on the curve.

The point of optimality is defined as the point which maximises their utility (i.e. minimises their negative utility).

Let (utility of missing flight)/(utility of spending an hour at the airport) = n

If n1 and n2 correspond to the points (x1, y1) and (x2, y2) on the curve respectively and n1<n2,

then x1<x2 and y1>y2

The more you prefer missing flights relative to spending time at the airport, the more your point of optimality will tend towards the left side of the curve.

The more you prefer spending time at the airport relative to missing flights, the more your point of optimality of will tend towards the right side of the curve.

As an added point, the concave shape of the trade-off curve demonstrates diminishing marginal returns.

Qualifications On Concept

Of course, if you’ve never missed a flight, it does not automatically mean you’re wasting time at airports. Many of us have not booked enough flights to have missed one even though we’re spending the optimal amount of time at the airport. Missing a flight is a probabilistic event after all.

That’s exactly why it was critical for the quote to qualify the 2nd clause with “probably”.

Some people have booked a great number of flights yet have not missed one because the utility to them of missing a flight is very negative relative to that of spending an hour at the airport. The word “probably” also accounts for this possibility.

To remove the word “probably” and retain technical accuracy, the quote would be: “Given that you do not have a radical preference for being present for your flight, if the probability of you missing a flight is virtually zero, you’re spending too much time in airports.”

It becomes less impactful due to its verbosity and technicality. And it’s not very precise (as seen by: “radical”, “virtually”).

Qualifications On Model

In the graph, the curve looks really smooth and satisfying. In actuality, it is not so perfect. There will likely be ridges of different gradients.

But the curve is a good approximation of reality. More importantly, the model defined by {y = e-kx, x≥0} is sufficient for the instructive purposes here.

That model does not map to real life one-to-one due to specific characteristics of the airport or airline, among other diverse factors. But uncovering those details is not the purview of this post.

For all 0 < P (event) < 1, the event may not materialise due to the very nature of probability. Nevertheless, P (event) is considered a cost because at the point of the decision, we deal with expected values. We do not judge decisions based on outcomes, but on expectation.

Implicitly, in all scenarios involving empirical events, we deal with probability, expectation and credence. We cannot be certain that tomorrow the sun will rise, the laws of gravity will remain unchanged and the universe will exist.

We may be confident enough to bet everything we have that they will, but we can never have metaphysical certitude.

But gravity is a fact! How can it be wrong?! The word “fact” means different things in the empirical and analytical realms. The difference between “2+2=4” as a fact and “gravity” as a fact can be negligible, nuanced or necessary depending on what you’re talking about. Most people relying on the former interpretation alone go through life without any issues.

When we decide whether to have fun at the amusement park tomorrow, we care about whether it will be sunny tomorrow but not whether the sun will rise, because only the former is indefinite enough to be worth the cognitive load of decision-making.

If we want to be really rigorous, there cannot be a vertical intercept where P (miss flight) = 1 when Hours Spent At Airport = 0. You may teleport into your airplane seat. It may not be permissible under the laws of nature we know, but who says our knowledge is complete? Who says the laws will not change? These are worth attention, but then we wouldn’t be doing economics.

The Pastiche

To refresh, the quote I conceived is “If you’ve never been a victim of fraud, you’re probably not trusting people enough.”

Replace y with “P (victim of fraud)” and x with “level of distrust” for the imitation quote: “If you’ve never been a victim of fraud, you’re probably not trusting people enough.” Exactly the same principles apply as the 2 quotes are perfectly analogous.

Note that x should not be replaced with “level of trust” as I change the logic structure of the statement’s 2nd clause from “too much” to “not enough”, so you need to use the converse of trust in defining x in order to neutralise the effect of a flip in the clause’s logic.

What It Looks Like In Print

Edit on 25 June

Someone replied to my letter. You can read it here.

One thought on “Airports ✈️, Banks 🏦, Cheating 💸 and Distrust 🤨”