The Foundational Idea

A way to find out whether there is too much or too little of something—pollution, people, violence or vaccines—is to consider the incentives the individual causing its production or consumption faces, and see how it compares to the costs and benefits of everyone else.

The Idea Applied Radically

Some have proposed a windfall tax on the companies who profit from war while others advocate raising taxes on the people who fund wars. Can we tax the people who are directly responsible for fomenting wars?

When a country like Russia attacks Ukraine, what does a leader like Putin who started the war stand to gain?

He can subjugate Ukraine, check the spread of NATO, demonstrate the strength of Russia…

That’s not wrong, but what can he gain?

He can achieve personal glory, the fulfilment of his nationalistic fervour, the cementing of his legacy, among other things. He stands to lose the obverse of those things too1.

But generally what he gains is more than what the average Russian citizen or soldier gains, and what he loses is less than what the average Russian citizen or soldier loses. The benefits of winning a war disproportionately accrue to the leader who initiated it while the ruin and suffering of war tend to hit the people harder. That’s a recipe for an over-creation of war.

Almost invariably, the person who instigated the war is better protected from its ills and perils than the people who fight, finance or live with it. When a decision-maker tends to attract greater benefits from a decision than the people his decision affects, and/or is better shielded from losses than those people, he will be inclined to commit more of that decision than is optimal for the well-being of the people, leading to too much of that decision.

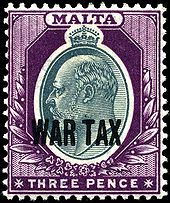

When faced with such incentive problems, we think of taxes. If we tax steel factories who profit from overproduction which damages the environment and hurts people, why don’t we tax politicians who profit from war which damages the world and hurts people?

The tax can be something like this, in the form of an agreement.

If the real purchasing power of the average citizen falls by x following a war, the Leader must relinquish half his total wealth.

OR

If 100,000 casualties are sustained in battle, the Leader must lose a limb not of his choice.

Such a tax will form part of the social contract of a society.

This tax will discourage military spending, further reducing the harms of armed conflict.

In any case, the details of the tax should reflect the situations people face in war.

The Leader who defends an invasion by refusing to surrender is culpable for a war just as the Leader who initiated the assault is to blame for a war. Their degrees of fault differ of course.

But the defending side of a military expedition has the same kind of incentive problem the offensive party has. Hence there would also need to be a tax agreement for the Leader who fights against an attack, just as there is one for the Leader who starts one. In other words, in an ideal world, both Putin and Zelensky need to be taxed. We cannot take for granted that citizens of a country want to make great sacrifices to safeguard their country’s sovereignty.

Presumably the tax for defence would be lower (possibly negative, making it a subsidy, depending on citizens’ inclinations) than that for attack, so there would be two separate contracts.

Conclusion

No anthropogenic activity comes close to war in terms of the scale and intensity of the distortion of incentives. The few individuals at the apex of an organisational structure get to decide how much immense suffering to allocate, but they scarcely share in those costs.

Footnote

1: Due to state-control of media in Russia, the extent of the losses may be less than the extent of the benefits as, acting in Putin’s favour, the former can be attenuated while the latter magnified (i.e. the benefits and their corresponding downsides are asymmetrical).

One thought on “A Kind of War Tax 💸”